Petrographic Motifs and Stratas. Photo or Graphic?

“(…) images can still be used to interpret the world, and if the world becomes so complicated that it is almost inseparably connected with the visual world, the interpretation, whether with images or interpretation, must make it its task to refine our world perception.” (Beke 239)

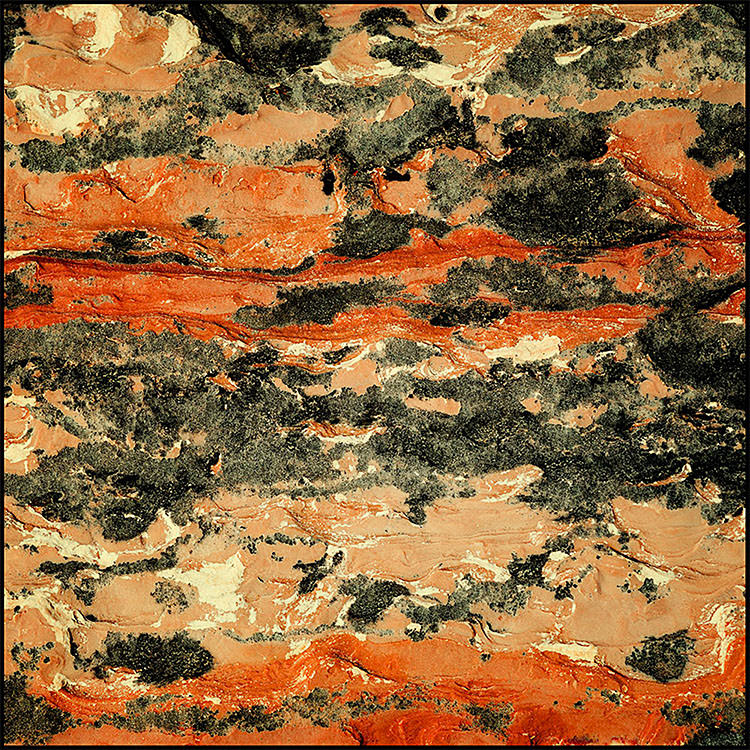

My intention is not to provide interpretation or commentary to the photo series titled Rock Surfaces (Rock Surfaces, Rocks II ). Instead, my reflections function rather as the extension of perception. Its inspiration comes from the photographic realism of mineral mosaics, rock drawings, geological stratifications, shapes made by the water, and from the surrealism of the natural vision (Summer), or maybe from the opposition between the two. My central question is: how can photographs discarding the idea of artwork evoke an artistic effect?

The birth of the photos is the result of spontaneous perception, of accurate observation, and not of an artistic objective. The close-ups are the visual substitutes of the object, of the shard of surface that is glimpsed. They are not the products of any artistic, technical or other types of special shaping or intervention. It is the unexpected vision of the surface and the surprise of the chemistry disclosed in the perceivable structure of the material, in the colourful strata and plies that bring them to life. The rock, the stonewall, the mineral sediment, the crystalline surface are all mute faces, material presences devoid of meaning. Visibility. I do not know what precedes the selection of the perceived, what makes the capturing of the sight unavoidable. What is certain is that even spontaneously, unwittingly the refined aesthetic sense of the photographer’s perspective is actuated. The perception of proportion, of constructedness, of the peculiar colour scheme, of decorativity and the ribbed surfaces, of facture in such situations and tracts, where the person passing through got either by chance or with a different intention.

The photographic capturing of the phenomenon becomes a cutout, it isolates the perceived phenomenon from its surroundings. No description or explanation complements it. The photo is merely the minuscule excised piece of the entirety of the view: of the island-like seashore, of the relief, of the slope, of the mountain, of the scree, of the rift. The mystery of the photography capturing the natural surface is enhanced by the objectless non-figurativity and the ornamentality. The photos analyzed here, mind you, are not pictures of the living nature, of the biosphere of creatures in motion. They are neither slowed nor fastened photos of events, but the surface drawings of the inorganic nature. The ensemble of perception, susceptibility, visual sensibility and the camera’s technical possibilities.

How do these cutouts devoid of events, of movements, of living creatures nevertheless persistently engage the attention of the viewer? And why does answering this question seem more difficult than the one referring to artworks? Does not the road seem perhaps more viable than the analysis of figural, perspectival artistic representations because we inherit the art theoretical and historical appreciations? In the Rock Surfaces, Rocks series there is no visual design, no perspective, just the random, incorrupt glimpse. The primal effect of the perceived upon the perceiver, then upon the picture’s viewer. The eye is magnetized by the surface that is formed by the subversive, constructive, transformative, ripping and stratifying energy of the natural forces. It seems as if the photos followed a mineral fantasy. Their beholder stands in awe in front of the beauty created by them.

Now I am distancing myself a little from the mystery of gazing the picture and from the unfathomable meanings of the photo. Instead I am attempting the imaginary reconstruction of the process making the photographic visualization possible. The observation of watery surfaces or rock patterns started from the gestures of perception, sensation, selection and exaltation, which was then followed by the enlargement resulting in this close-up. From the perceived a photographic experience was born. This is what the photos impart with us, this is what should be answered by the formulation of the percipient’s viewing experience. Meanwhile we are overwhelmed by literary examples bearing powerful scenic perception, such as W. G. Sebald’s. On his tireless and endless strolls he was always carrying his camera on his shoulders. And then he embedded his photos of vistas capturing desolation and exhaustion into meditative essays. Picture and text together became the expression of the continent destroyed by war and of his own sombre life experience. “But the closer I came to these ruins, the more any notion of a mysterious isle of the dead receded, and the more I imagined myself amidst the remains of our own civilization after its extinction in some future catastrophe” (Sebald 237). Christoph Ransmayr also expresses a dark experience of history in his vision of the world after nature.

From the visionary and imaginary projections I will now return to my main question. To the question, why does the image of a rock surface, of a “rock pattern” seem inexhaustible, our instinctive answer could be: because the amalgam of yellow, crimson or even blue and grey strata evokes a graphic experience. On the bluish-greyish surfaces of other photos it seems like we recognize the contours of the primal eddying or of some sort of stone-like whirlwind. It is obvious in both cases that the analogic thinking came into play. In the interpretation of the scene we resort to the gestures of comparison. On the natural vision that has been randomly revealed to us we identified known shapes, and then we created similes, metaphors. The other interpretive possibility would be the process of photo description, through which the objectless, material and coloured surfaces would be accompanied by a detailed text. The third version could be the narrativization of the motionless vision, forming the mute segment of the landscape into a narrative. Nevertheless, the question is whether our observations as beholders would be genuine, or the very gesture of verbalization would distance us from the effect of the elemental impression.

Photo-artistic research, furthermore, photo theory, photo interpretation provide numerous guidelines for our ruminations. Susan Sontag’s engaged socio-critically minded conception of photography cannot have a substantial significance in the coherence of these photos of peculiar, inorganic natural surfaces. Nevertheless, in her following claim we are definitely following the same direction: “Everyday life apotheosized, and the kind of beauty that only the camera reveals – a corner of material reality that the eye doesn’t see at all or can’t normally isolate; or the overview, as from a plane – these are the main targets of the photographer’s conquest” (69). The art historian Daniel Arasse’s work entitled On n’y voit rien. Descriptions encompasses in its title the fact that essentially we see nothing, or barely anything of the thing we regard as artwork. But isn’t it possible that the mode of perception is numbed just like this? Isn’t our susceptibility toward the aesthetics of the natural view diminishing, too? The “cursory glance” excludes immersion, and initiates superficiality as the norm. The swarm of people constantly captures themselves and their every step just for the sake of capturing with the lenses of their mobile phones. This is how they float through museums, beaches, cities, their whole lives.

The observer of Rock Surfaces and the one capturing the view represents a different attitude. He is closer to André Kertész: “The camera is my tool. Through it I give a reason to everything around me” (163). The experience of the photographer can bring us closer to the understanding of the photos of rocks representing the starting point for contemplation. Kertész’s thought can be found in Sontag’s rich collection of quotes, together with the following:

Photography is a system of visual editing. At bottom, it is a matter of surrounding with a frame a portion of one’s cone of vision, while standing in the right place at the right time. Like chess, or writing, it is a matter of choosing from among given possibilities, but in the case of photography the number of possibilities is not finite but infinite. (John Szarkowski 150)

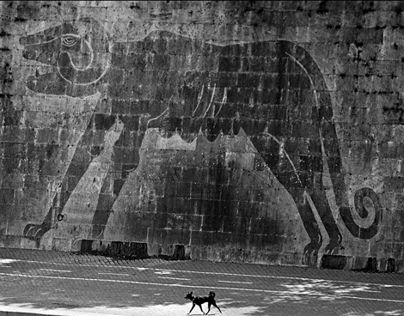

The close-ups of the views of rocks inadvertently evoke in us the memory of archaic rock drawings, in which it was the cave’s wall itself that conveyed the rocky background for the created picture. In the photos analyzed now, however, it is the mineral strata that do the drawing, carve forms and snick the immaterial surface. In Walter Benjamin’s contemplation the photograph is the alternative for lithography.

Graphic art was first made technologically reproducible by the woodcut, long before written language became reproducible by movable type. The enormous changes brought about in literature by movable type, the technological reproduction of writing, are well known. But they are only a special case, though an important one, of the phenomenon consid ered here from the perspective of world history. In the course of the Middle Ages the woodcut was supplemented by engraving and etching, and at the beginning of the nineteenth century by lithography.

Lithography marked a fundamentally new stage in the technology of re production. This much more direct process-distinguished by the fact that the drawing is traced on a stone, rather than incised on a block of wood or etched on a copper plate-first made it possible for graphic art to market its products not only in large numbers, as previously, but in daily changing variations. Lithography enabled graphic art to provide an illustrated ac companiment to everyday life. It began to keep pace with movable-type printing. But only a few decades after the invention of lithography, graphic art was surpassed by photography. For the first time, photography freed the hand from the most important artistic tasks in the process of pictorial re production-tasks that now devolved upon the eye alone. (Benjamin 102)

We are back at the capacities of the eye glancing into the lens. Does the photographer’s seeing sight have a connection to the things of the nature that is being created and is effected? Or it pretends like it does not have to know about the emergent (natura naturans), since with the click of the camera it creates just a minor record of the memorable glimpse. According to Daniel Arasse the role of the perspective, which has been the defining factor in the creation of visual images for five centuries, is taken over by the camera by the fact that „ just imitates the principle of perspectivic representation: there is one eye and every line is pointing towards a point that is the projection of the eye to the plane of imaging”. The photos of Rock Surfaces do not only differ substantively from the above mentioned because they are not studio photographs, panel pictures, or paintings, but because they were created in the spirit of a different kind of sensibility. They surpass perspective because it is not their guideline. The eye does not design, but it selects and inserts into the close-up which can be captured. It analyzes, leaves speechless. It does not comment, but presents the rugged surfaces, the graphite-shaded horizontal strata, the rocks settled into wavy wrinkles, the primordial tracts. There is no technics, no interference, no shaping, no framing, no figurativeness. The surfaces exist purely of themselves, and the only thing that happened was that somebody perceived and captured them. And then we seem to inadvertently find ourselves in one of Jackson Pollock’s paintings: in the eternalized sea of paint-drops that his two-dimensional canvases became with drip. The reliefs urge us to touch them even on the reproductions of paintings and photographs. The tactile thrill of Rock Surfaces is triggered by the geological, among others precisely by the work of erosion. The unfathomability of the view, the forms and abstract non-figurativism of the inorganic material renders the gaze that aspires for understanding persistent. Regardless of the photographer’s will.

Traduction by Noémi Albert

Works Cited:

Arasse, Daniel. On n’y voit rien. Descriptions. Paris: Denoël, 2000.

Arasse, Daniel. Histoires de peintures. Paris: Denoël, 2004.

Beke László. Utószó. In. Susan Sontag: A fényképezésrol. Trad. Anna Nemes. Budapest: Európa, 1981.

Benjamin, Walter. Selected Writings, Volume 3, 1935-1938. Trad. Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn. Series editedby Howard Eiland, Michael W. Jennings, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 2002.

Sebald, W. G. The Rings of Saturn. Michael Hulse (trans.). New York: New Directions, 1998.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Picador, 2001.